Remote ID for drones is basically like a digital license plate for drones. Remote ID technology on drones allows a drone’s identification and location information to be broadcast in an effort to better incorporate drones into the manned airspace.

Drone Remote ID Basics

While the basic idea behind Remote ID on drones is to provide agencies like the FAA the ability to identify drones in the United States airspace, there is also concern in the drone community that Remote ID solutions will destroy pilot privacy by allowing the general public to access drone pilot information.

While privacy is a concern, the FAA has made it clear that remote ID is the only way it can see to fully incorporate drones into manned airspace, specifically as it relates to flying drones beyond a pilot’s line of sight. Without the use of this technology, drones would be relegated to commercial work that always requires a line of sight. This would prohibit drone deliveries as well as more complex inspection missions that could be accomplished in the future using drones with better battery life.

I’ve talked about transponders before and how they’re used in manned aviation to broadcast an aircraft’s location in airspace. Some forms of airspace even require a manned aircraft to have a specific type of transponder in order to operate within the airspace.

Remote ID on drones is like that. At this point, you are required to register your drone with the FAA (Check out my article on drone registration) but aside from registering your drone, the FAA (or other agencies internationally) is simply unable to identify your drone when it is in the sky. Remote ID is the answer to this question.

Types of Remote ID

There are several types of Remote ID, including broadcast and network based remote ID. Each type of Remote ID system has benefits and drawbacks, all of which will need to be reviewed by the FAA before it puts anything in place.

Broadcast Based Remote ID

Broadcast based Remote ID looks to the hardware (the drone) to transmit a signal that can then be viewed and consumed by parties with received capabilities. There are several problems with this type of Remote ID system. First, it is often proprietary and probably doesn’t operate between hardware manufacturers. Second, while this solution works for identifying drones in a small, contained area, when you are talking about a solution that could be used to allow drones to fly beyond line of sight, this solution would probably require too many receiver units in place to make this type of Remote ID possible.

In practice, broadcast based Remote ID would be something like DJI’s Aeroscope or Intel’s Open Drone ID. With Aeroscope, you actually need to have the Aerospace hardware. They do sell a portable unit, but I had a hard time finding a price and this is really only being marketed to airports and agencies that would need to be able to detect drones.

The Verge put together an interesting video on DJI’s Aeroscope system is you’re interested (below). The Verge video indicated that the DJI Aeroscope system (or I guess similar broadcast based Remote ID systems) only works with drones that have been registered. So if a bad actor out there wants to do something with a drone, I’m assuming they could bypass detection by not registering. To be fair, the video doesn’t really say whether this means registration through the FAA or registration with DJI. Either way, it seems like detection could be avoided here.

Network Based Remote ID

A network based Remote ID system seems like the way this system will unfold and actually be put into place. First, like our cell phones, this system is networked (as you can imagine by the name).

This type of system has the potential to be used without the need for additional hardware, which makes the barrier for entry a lot less. In fact, Airmap, Kittyhawk and Wing (Google’s drone division) all recently demonstrated a system they call InterUSS Platform. USS stands for UAS Service Supplier, and refers to a service provider like Kittyhawk or Airmap that allows you to get FAA airspace approval through the LAANC system.

The idea is that each drone flight would essentially be run through whatever USS you typically use and the flight can be tracked and seen publicly. The USS collects the necessary drone information, runs it through the networked InterUSS platform and transmits it to other Remote ID apps. In the recent demo, this even included bystanders. So long as you have the necessary Remote ID app, you would be able to see the drone flights.

One of the beautiful things about this system is that it is open source, meaning that any number of developers could become a USS and tap into the same interface. It wouldn’t matter who the manufacturer of the drone is, just that the person flying the drone was hooked in through a USS that uses the Remote ID system. This would allow for quicker adoption.

I guess the downside to a system like this is that it requires some sort of buy-in by the drone pilots. Granted, most people are trying to follow the rules, but if someone wanted to do something nefarious with a drone, would they really go to the hassle of logging in to Airmap before they did it? Probably not.

Does Remote ID Sacrifice Privacy for Safety?

Before you get all up in arms about how the drone industry is becoming over-regulated, it is important to state a few things. In the network based Remote ID system I just talked about, it seems that the information available to the general public about your drone flight is pretty limited. Even when I check the current drone traffic on the Kittyhawk app now, all I am able to see is location, heading and altitude.

And with the DJI Aeroscope system, although someone with the hardware could see who the drone is registered to and contact information, this would first require the Aeroscope hardware. It’s not cheap. All of this means that its unlikely that someone with a cell phone will be able to download an app and have all of your information if you are flying a drone nearby.

While privacy concerns could be a real issue, I’m just not sure that there is a way to advance drone technology to things like beyond line of sight without the use of a Remote ID system.

When you consider commercial air traffic generally, all commercial aircraft file flight plans before taking off. As part of this system (which allows the aircraft to be tracked and managed by air traffic control), the aircraft is essentially handed off to different controllers throughout the whole flight, in order to make sure that the airspace they are flying in is not overly crowded and that there is enough room between all aircraft.

When we consider what drones are capable of (and I’m not talking about photographing a house) it will be entirely necessary to make sure that drones are flying safely and with proper space between them when they are delivering consumer products or way farther down the road, when they are (possibly) working as a type of air taxi. At that point they are no different than other manned air traffic.

Remote ID will be put in place in the future, the only question is what system and how will it’s use be required? And it is this exact question that led the FAA to release its recent Remote ID proposal.

What is The FAA’s Remote ID Proposal?

On December 31, 2019, the FAA published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NPRM”) about remote ID. I won’t get into too many of the details about how the FAA works and the bureaucracy of administrative law, but suffice it to say that an NPRM is something akin to a heads up about what the FAA would like to do. Now that it’s been published, anyone can comment on it. Feel free to comment. In fact, if you have read and understand the NPRM and you’re a drone pilot, it’s probably in your best interest to comment. This NPRM already had over 1,000 comments within three days of being published, so I can imagine the number of comments by the time the comment period expires in March will be in the high thousands.

To be clear, the purpose of the comment period is to allow any interested party to be heard. Despite what you may initially think, these comments matter and the FAA won’t ignore them. In fact, after the comment period ends, some poor bureaucrat’s job (actually a whole team of them) will be to comb through the comments to see what is being said. The FAA will then take those comments and use them to craft a rule that seems to address the most common critiques and industry issues. Don’t complain about not having a voice if you don’t take the time to comment now.

So far, I’d say the response from the drone industry and privacy advocates has been pretty negative, to say the least. But before we get into the commentary, let’s just take a look at exactly what the FAA is proposing.

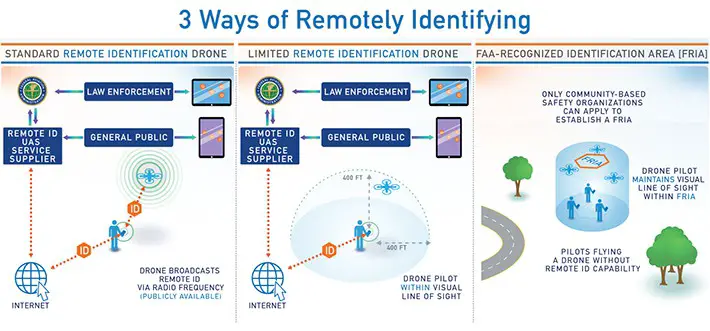

The FAA is proposing three ways that a UAS (which I’ll call a drone) can meet the Remote ID proposal operating requirements:

- Standard Remote ID

- Limited Remote ID

- UAS without Remote ID

This chart comes from the FAA (link to FAA article on Remote ID for Industry).

Standard Remote ID

This version of Remote ID is the least restrictive as far as how and where a drone will be able to fly. Essentially, a drone will be operating under the “standard” remote ID when is can connect to the internet and transmit that information to a Remote ID USS and also broadcast identification and location information via radio frequency. The NPRM says:

Standard remote identification UAS would be required to broadcast identification and location information directly from the unmanned aircraft and simultaneously transmit that same information to a Remote ID USS through an internet connection.

I covered what a USS is in my previous article on Remote ID but it is basically the service that will allow third parties to see all drones that are transmitting their flight information. Think Airmap or Kittyhawk.

The good news is that the proposed rules allow for a drone that can broadcast via radio frequency to fly without an internet connection in places where one does not exist so long as the drone continues to broadcast via radio frequency during its flight.

The other good news is that the proposed rule doesn’t have any specific hardware or internet connection requirements, which is a good thing because this means that it will likely be easier for an older drone to comply with the standard remote ID requirements. The proposed rule specifically states:

For both standard and limited remote identification UAS, at this time the FAA has not proposed any requirements regarding how the UAS connects to the internet to transmit the message elements or whether that transmission is from the control station or the unmanned aircraft.

This may seem like a small detail, but a requirement that the drone itself be able to connect to the internet could really cause problems since most drones are only connected to the internet through the ground station (your controller). Forcing the drone itself to be connected to the internet would require drone manufacturers to incorporate this technology into the drone itself.

In fact, in the NPRM, the FAA estimates that 93.3% of the drones that are “registered to part 107 operators…may have technical capabilities to be retrofitted” through some sort of software update so that they can comply with these proposed regulations. Specifically,

The FAA identified the top-10 registered aircraft by producer and researched registered model specifications online. The FAA found each of the registered models within this group had internet and Wi-Fi connectivity, ability to transmit data, receive software uploads, and had radio frequency transceivers, among other technology such as advanced microprocessors.

So, what if your drone can’t work under the “standard” remote ID requirements? Let’s talk about limited remote ID.

Limited Remote ID

The second way that a drone can meet the Remote ID requirements is to fly the drone no more than 400 feet from its control station. In this case, the drone is not required to broadcast information via radio frequency, but instead is only required to transmit information through the internet. The NPRM says:

Limited remote identification UAS would be required to transmit information through the internet only, with no broadcast requirements.

So, under this standard, a drone could not be flown at all in places that do not have an available internet connection. But it also can’t be flown more than 400 feet away from your controller. Obviously, this is well within your line of sight and seems super constricting. Maybe this number will change after the comment period. If not, it seems like it could cause a problem. I frequently fly my drone much farther away from my controller than 400 feet.

What if your drone can’t connect to the internet at all? You might be even more limited in what you’re able to do with your drone.

UAS Without Remote ID (FRIA)

There is a third category for drones that do not or cannot broadcast information via radio frequency and/or transmit via the internet. The FAA calls this an FAA-recognized identification area or a FRIA. This is the most restrictive option, essentially only allowing the drone to be piloted at specific FAA designated areas, called FRIAs. These are basically the Academy of Model Aeronautics fields that already exist as well as any new fields that are approved by the FAA.

What’s the difference between Standard Remote ID and Limited Remote ID?

Well, just based on the NPRM, the difference is that a drone operating under the standard remote ID requirements can broadcast the required information in addition to being able to transmit it over the internet while a drone operating under the limited remote ID requirements is only transmitting this information over the internet.

The real question though is: what difference does this really makes for drone pilots?

Well, the answer sort of depends. If you’re flying a newer drone, aside from logging in to a USS to transmit the required information over the internet, there may not be a big difference for you. Manufacturers like DJI are very likely to put out a software update for their drones that will handle the broadcast via radio frequency (and possibly even incorporate the USS transmission within the app) for drones that can do so.

If you’re flying an older drone or one that is unable to connect to the internet, your options seem like they will be pretty limited. Either you fly indoors or you go to a FRIA to fly your drone. The FAA likely had a hard time calculating the number of hobbyist drones that are able to meet the remote ID proposal requirements because as it stands, a hobbyist drone pilot can register a number of drones under one registration number. This leads us to our next point.

What information is required to be transmitted?

The NPRM says that the following must be broadcast

- One of the following:

- The serial number assigned to the unmanned aircraft by the producer.

- Session ID assigned by a Remote ID USS.

- An indication of the latitude and longitude of the control station and unmanned aircraft.

- An indication of the barometric pressure altitude of the control station and unmanned aircraft. (Barometric pressure of the unmanned aircraft only required for standard remote ID).

- A Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) time mark.

- An indication of the emergency status of the UAS, which could include lost-link or downed aircraft.

What does the FAA’s Remote ID Proposal Mean for You?

In addition to these limitations, the FAA’s remote ID proposal also changes a few other things. One of those things is the registration requirements. Because the FAA is looking to put remote ID in place to be able to track drone flights, each drone will need to be registered under its own registration number, even if you’re a hobbyist pilot. Naturally, you’ll be paying for each individual registration just like Part 107 pilots do.

But this is probably not the only cost. Servers aren’t free and in addition to being registering each drone individually, the requirement that all drones broadcast information over the internet means that USS services will probably start to cost money, likely in the form of a monthly service charge in order to access their service and properly transmit the required information. We really don’t know for sure, but the FAA seems to point to that as a possibility.

In reality, if these rules don’t change, they could have a pretty major impact on hobbyist drone flight in particular. I’m not sure that most hobbyists will want to either pay a service to broadcast their location so that they are in compliance and/or drive to an AMA field to fly their drone. In some instances (probably most FPV drones), the pilots will have no other option than to find a local AMA field. This could cause some real problems.

Are there any privacy issues with this remote ID proposal?

This is where a lot of people started to freak out a little bit, and despite the fact that I think privacy is a real issue here, I think the panic is overblown for a couple of reasons. First, we have to remember that these are just proposed regulations. The comment period is in place for a reason and this allows people with an interest in drone technology to make their voices heard. I encouraged you at the beginning, but go comment on this proposal!

The other reason I don’t think this is likely a big deal is because I would bet that we land at a comfortable middle ground, where law enforcement is able to see your contact information but not the general public. And that seems to make sense to me.

Maybe my problem is just that I’ve not been attacked in public for flying a drone. I’ve seen this concern voiced in more than one Youtube video and article about the Remote ID proposal. Is that really an issue? I’ve flown hundreds of drone missions, some of them in some pretty strange places. We even had some jobs in the more rural parts of my home state (Kentucky) and I’ve had literally zero problems with people. Sure, we’ve had a few concerned individuals, and others that wanted to ask all kinds of questions, but I’ve never once felt threatened. If we are truly worried that someone will download an app to be able to locate a drone pilot only to try and start a fight, I must be living in a different world because that seems like it’s just not an issue to me. And honestly, I’m not sure that I’m so concerned about having my location broadcast at all when I’m flying a drone. We give our phones the ability to use location data all the time and don’t think twice about it. Granted, they aren’t publicly broadcasting our location, but in some instances I’m sure they could be.

Yes, privacy could be a concern but I’d prefer to wait until we see what happens after the comment period before we all collectively lose our minds.